Purim and the Book of Esther

Part I. Purim and the Book of Esther – Where’s the Evidence that the Story is Real?

Note that this article was a lot longer than anticipated. Because of its unwieldy size, I have broken it down into four Parts (with subparts) as follows (and will be published a few days apart):

- Part I. Purim and the Book of Esther – Where’s the Evidence that the Story is Real?

- Part II. Purim and the Book of Esther – Origin, History, and Evolution of the Holiday

- Part III. Purim and the Book of Esther – Laws, Customs, and Traditions

- Part IV. Purim and the Book of Esther – History and Origin of Hamantaschen (and Recipe)

At the end of this month Jews around the world celebrates a woman’s courage that helped to save the lives of thousands of Jews. This celebration is called Purim (which occurs on the 14th day of Adar in the Hebrew calendar). There is no mention of this holiday in the Torah / Bible, nor is there is any evidence that the events in the book (or the people described therein, including the heroine) ever existed; at least no direct historical proof has ever been found. Nonetheless, there are a few loosely interpreted tangential pieces of “evidence” that I will lay out later in this article. For a holiday that has neither biblical origin nor historical providence, there are quite a few mitzvot, traditions, and interesting minutia that have become part of its festivities. If you make it to the end of this article (its a long one), you will be treated to the origin and history of cookies – including one that has become associated with this holiday – hamantaschen.

A. What is the Book of Esther?

1. The Story of Esther In Religious Liturgy

a. Judaism.

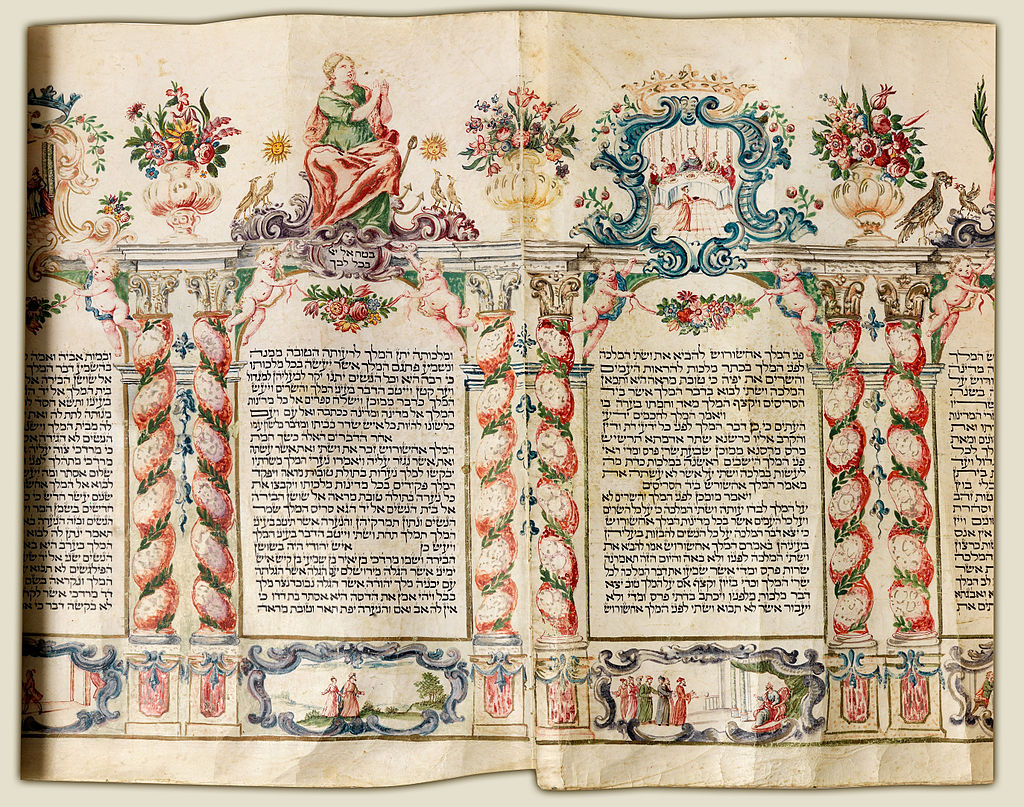

Regarding religious liturgy, the Book of Esther is one of the books within the Tanakah (Jewish Bible). It is in the section called the Ketuvim (“Writings”). This story is one of five scrolls, called Megillot recited on various Jewish holidays. It is interesting to note that the Book of Esther was not found among the Dead Sea Scrolls in the Qumran caves, which means that the Essenes (an early Jewish sect) had not adopted it or they broke away from the main religious group prior to it being added. But it is of no surprise that it was not included with the scrolls. Early Jewish leaders in the 1st and 2nd centuries, such as Samuel of Neharda (Samuel bar Abba), had argued against its inclusion (so the Essenes may have know about the story, but just did not want it as part of their liturgy).

b. Christianity.

The Book of Esther is also included within the canons of the Old Testament in Christianity. The version read by the Roman Catholics includes an additional six chapters that are not part of the Jewish and Protestant version (believed to be apocryphal (i.e., not authentic) – these additional chapters were believed to have been added to provide a religious context, highlighting Esther and Mordechai’s devotion to G-d). The Catholic canon is referred to as the Greek Book of Esther (more is described later).

Even in Christianity, its adoption was controversial. One issue with its adaptation is its Jewish theme, as Martin Luther wrote in Werke, “I am so hostile to the book and to Esther that I wish they simply did not exist, for they Judaize too much and have (and reveal) much pagan bad behavior.”

c. Islam.

Although the Book of Esther was not incorporated into the Quran, it does include a character named Haman (who worked for the Pharaoh, in Egypt, and timed to about an eon earlier. The story of Esther was known throughout the pre-Islamic Arab world and continued though some sects of today’s Muslim world (especially in Iran). There is even some speculation that Abraham’s brother Haran is Haman in the Islamic texts.

2. Summary of the Book of Esther Story

If you have never heard the story (or gone to a reading on Purim and did not understand the Hebrew version), a summary is as follows: Mordechai (a religious leader, and/or member of the King’s staff [his position/title is disputed among religious scholars]) did not bow to a high-ranking official of the King (Achashverosh) named Haman. Haman got upset. Modechai was Jewish, and Haman decided to take out his anger on ALL of the Jews living in the land (Persia) . . . . . by killing them all. [Fast Fact: The earliest known use of the word “Jew” to describe someone of the Jewish faith (instead of Hebrew or Israelite) was in the Book of Esther 2:5, in reference to Mordechai.] He chose a date for the murders through the use of a lottery (the Hebrew word for lottery is pur – which is how the holiday got its name); the day chosen was the 14th of Adar in the Hebrew calendar. [Reader’s Note: remember this date; it becomes a focal point when discussing some of the theories of the origin of this holiday, and it explains some of the unique intricacies of its observance.] In comes Esther, a relative of Mordechai, who just became the queen (she “won” a contest after the former queen, Vashti, refused to obey the king and show her nakedness to a group of men and was put to death for her refusal). Through Esther’s influence and heroism (e.g., appearing before the king – twice – without being summoned, which held a penalty of death) she convinced the King of Haman’s evilness, and saved the Jews. Although the King could not withdraw the decree, he allowed the Jews to defend themselves (which they did). At the end of the story Mordechai implores Esther (via a letter) to have all Jews celebrate this event. [FYI – To add irony to the story’s conclusion, Haman was hanged on the same gallows he had built especially for Mordechai.]

The Greek Book of Esther version (as adopted by the Roman Catholics), is thought to have been written originally in either Hebrew or Aramaic prior to being translated into Greek, which then included six additional chapters to the Hebrew version. Some of the “new” material includes an introductory chapter in which Mordechai has a divine dream of Haman’s plot, prayers by Mordechai and Esther, and a conclusion showing that Mordechai’s dream had been fulfilled. Also note that the spelling of the names for some of the main characters in the various versions has led to confusion. This has been one of the issues to prove if the story was in fact true and based on living people in history.

B. Was the Book of Esther Historically Accurate?

There have been critics of the veracity of the Book of Esther for centuries. Criticism goes back to Johan Salomo Sempler (a German biblical commentator) in 1773 in Apparatus ad liberalem N. T. interpretationem. One of the toughest hurdles for biblical scholars to overcome is the lack of direct evidence of the names of the people in the story do not match (or at least only tangentially) known rulers in history. In addition some of the events in Esther’s story do not seem to match-up with know historical events.

1. The Evidence for the Book of Esther Being True

Although most of the scientific and archeological community do not believe that there is any truth to the story told in the Book of Esther, there are some that do. One of these believers is archeologist Gerard Gertoux, who has, through research, re-written the ancient chronological timetable and explains how the story Esther fits into history.

Other evidence for the truth of the story includes:

- Unlike other books in Jewish liturgy, it is written as a historical description and the name of G-d is not mentioned once. In contrast, the name of the king is mentioned 190 times in 167 verses

- There is conformation, or at least collaboration for some of the events (or at least the existence of a king of Persia, and a capital city of Susa which corresponds with Shushan in the story) at that time by a number of sources written at the time. They include:

- Herodotus, History of the Persian Wars (~440 BCE);

- Ctesias, Persica (early 5th century BCE);

- Xenophon, Cyropaedia (~370 BCE); and

- Strabo, Geographica (~20 BCE)

- Some of the information about the king have similarities with a known Persian ruler names Xerses:

- Xerses controlled a huge empire

- Xerses has a temper

- Xerses threw extravagant parties w/ lavish parties

- The Persians have a very efficient postal system

- Because the ancient writers were not witnesses themselves, and because they wrote in a different language: names, dates, and details may have been changed or modified which makes it difficult to match up various names that may be spelled differently.

- Some words used in Book of Esther are “identified as Persian”

- Scholars are not always sure of its original linguistics when scholars find Jewish spelling of non-Jewish names, because of the language of the story, its various translations, and different characters, it makes it hard to collaborate and identify them

- Achashveros may have been- Xeres/Khshayarsha

- Due to an initial interpretation of cuneiform, the name of the King was Xeres, in 19th century they found that it is pronounced as Khshayarsha, which is linguistically “close” to Achashverosh

- Achashverosh was the king from about 486 BCE to 465 BCE, which is about the time between the rulers Daryavesh (Darius I) and Artachshasta (Artaxerxes) as referred to in the Book of Esther.

- A foundation stone at the Palace of Persepolis lists the lands ruled by Achashverosh, and it corresponds to the lands listed in the Book of Esther [note: there is discrepancy as to dates – the events of the Book of Esther may have occurred in the 12th year of Xerxes’ reign while the stone’s inscriptions may have been recorded only until the 7th year]

- The name Esther and the name Amestris (the wife of Xerces) are very similar

- Xeres may have had multiple wives, with Amestris being the primary wife, and Esther being a minor one

- According to Herodotus, the father of Amestris was a military commander. Esther’s cousin/guardian/father/uncle (depending on version of the story) was Avichayil – which is very close to the Persian word for military commander.

- The Name of Mordechai has been found in Persian documents of the time period – but is it the same one in the Book of Esther? Also mention of a Marduka (a high level accountant in Shushan – is it Mordecai, or is this person at that time, or even a Jew?)

- Archeologists have only scratched the surface of uncovering the annals of history. Just because evidence has not yet been found does not mean that it does not exist.

- There is a festival celebrated by Jews based on the story in the Book of Esther – why would they have an annual celebration (one that is not discussed in the Bible) if there was not at least some shred of veracity?

- Is it just coincidence that the son of Xerxes, Artaxerxes, was very lenient in his rule towards the land of Judea (where the Jews lived) if he were not the [alleged] son of Esther?

- This theory goes against the grain, or goes against politics of the leading archeologists or certain institutions, and therefore would not be advanced such theories such as those of Gerard Gertoux.

- In Hamadan, Iran there exists, what is known as, the Tomb of Esther and Mordechai. It has been revered as such for centuries – so there must be a speck of truth to the tale. [This is described in more detail below.]

Looking at each fact individually does not prove anything. However, when you look at all of the facts in their entirety, a glimmer of Esther’s existence does shine through.

a. Tomb of Esther and Mordechai

The fact that there is a place called the Tomb of Esther and Mordechai (or the Tomb of Mordechai and Esther) provides additional circumstantial proof of their existence. One may argue that there has to be a reason why the place was named after these biblical heroes hundreds of years ago. It is located in Iran in the Hamran area.

The Tomb of Esther and Mordechai is a pilgrimage site for both Jews and Muslims (in 2008 the Iranian government had deemed it a “National Heritage Site” – however, protection by the government was removed in 2011 after a student demonstration against Israel), although predominantly by adherents within Iran (the site it is not mentioned in most Jewish literature). The earliest mention of the tomb was by Benjamin of Tudelia in the 12th century, and the mausoleum itself was built in the 1600s. However, some travelers to the tomb have noted inscriptions of 1140 (CE) and a possible date of 1390 during a refurbishment. [Note: The site was the target of terrorists in 2020, when they tried to set it on fire. According to sources the tomb suffered very minor damage.]

It has been noted in a few articles that in the 20th century, a French explorer searching a niche at the site found jewels, including a crown, which is believed to have been that of Esther. However: I am unable to find a verifiable source for this. What I did find is that in 1901, French archeologist Jacques de Morgan uncovered a tomb of a woman in Susa (Susa, an archeological site of an ancient city located in Iran, is thought (by some) to be the city of Shushan), which included jewelry and a crown-like item (some believe it is a necklace), and none of the items include depictions of deities (forbidden by Jewish law) – and the only identifiable name found near the tomb was that of Xerxes; which have led some to believe that this is the tomb of Amestris (whom has been associated with Esther); the items are now in the Louvre – what I cannot find is whether this tomb is located in the same vicinity as the Tomb of Esther and Mordecai.

Archeologist Ernst Herzfeld believes that the tomb of Esther and Mordachai is actually the tomb of Shushandukht, a consort of a Sasian king (Yazdegerd I), and the daughter of Huna bar Nathan (also known as Rav Huna), a Babylonian rabbi and leader who lived during the 4th century.

It is also interesting to note that there is a second (alternative) location believed (by some) to be the burial place of Esther and Mordechai in the northern Israeli city of K’far Bar’am. There has not been any evidence uncovered, besides stories and local tales, that either of these burial sites are either Esther or Mordechai’s final resting place.

2. The Evidence That the Book of Esther is Untrue

- No evidence of the names of the people mentioned in the Book of Esther correspond directly to any names found by archeologists or historians (only tangentially, as mentioned above).

- Any of the ancient scribes that wrote of the Persian king did not personally witness any of the events, and may have relied upon rumor, conjecture, and literary license to create the “history” they described. In fact, Herodotus (an Greek historian in the 5th century BCE) has been called the “Father of Lies.” Herodotus, and all of the ancient writes many times were or could have been biased in their writing.

- The Talmud’s (Jewish law) timeline is different than the book of Megilla (Book of Esther); they have placed Achashverosh reining between the reigns of Koresh ad Daryavesh (contradictory to most historians) [see Talmud, Meg. 11b). [Although note, Gerard Gertoux describes why there is such a discrepancy of rulers and dates, and how they can be correlated.]

- There is no evidence (or corresponding writing at the time) of persecution of Jews at that time in Susa region of Persia

- There is evidence that the queen of Xerses was Amestris, and no mention of an “Esther” has been found; nor a mention of a second name she is called – “Hadassah”

- There are a number of individual in government positions or related to the king listed by name in the Book of Esther. None of the names in the list, which include: 7 eunuchs, 7 princely advisors, and 10 sons of Haman, have been collaborated with other evidence)

- From the evidence that traditional historians have been able to ascertain, Persian queens could only be chosen from within seven noble families. [Although note some believe that Esther may be of a high-born pedigree.]

- There is a long-time belief that the holiday of Purim was adapted by the Jews from the Babylonian New Year’s festival in Sacaea (called Zagmku). It is a holiday where citizens would feast and drink; which coincidentally is held about the same time as Purin. According to historian James George Frazer, the Babylonian celebration included the burning of a man (and later may have been modified to be a hanging). Note that the holiday of Purim had been called “Burning of Haman” in early historical texts. Of further interest is that it was held in connection with the worship of the deity Marduk, or Merodach, which is similar in name to Mordechai. It also just happens that another Babylonian deity of this era was named Ishtar (which sounds very similar to Esther).

- The story may be one that had taken root from an older Babylonian tale since the names Esther and Mordechai are very similar to the ancient Babylonian deities Ishtar and Marduk.

The provisions above provide some pretty solid facts disproving the existence of Esther and her story of heroism. For many believers, they just take it on faith, others believe that it was based on an actual person or event, but the truth of it has faded through time, for others it is just a good story.

3. Theories that the Book of Esther was a Parable or Allegory

There are some that believe that it may have some tenets of truth at its base, but has been changed through the years or the story may have been written as a parable to teach a lesson, or a story to provide unity or connection to Jews in the diaspora, such as the Book of Daniel, Book of Judith, or Book of Tobit [the latter two are not included in Jewish liturgy, although fragments of Tobit were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls.]

Some believe that the Book of Esther was a combination of two stories, which is backed by the number of “two’s” found in the book, for instance:

- Esther has two names (Esther and Hadassah)

- Two banquets

- Two lists of seven names are provided

- There is a second house

- Second group of virgin candidates

- Esther’s two dinners with the king

- Esther risked her life twice by appearing before the king unsummoned each time

Many scholars believe that the book was merely a fictional historical novella (with some non-fictional background of the time). These books were popular during that era. [Note: At some point I may research novellas written in ancient times – keep a lookout for it.]

There you have it – the proof (although slim) for the story having some validity, and the case against the Story of Esther. Belief is an individual matter. The next part of this article covers the history of the holiday of Purim. It’s possible origins and evolution of its customs and traditions may a little different than what you may have always thought.

To read a different part of this Article, click on the desired link below:

- Part I. Purim and the Book of Esther – Where’s the Evidence that the Story is Real? <current>

- Part II. Purim and the Book of Esther – Origin, History, and Evolution of the Holiday

- Part III. Purim and the Book of Esther – Laws, Customs, and Traditions

- Part IV. Purim and the Book of Esther – History and Origin of Hamantaschen (and Recipe)

[A compiled list of sources for this article appears at the end of Part IV]

7 thoughts on “Part I. Purim and the Book of Esther – Where’s the Evidence that the Story is Real?”